|

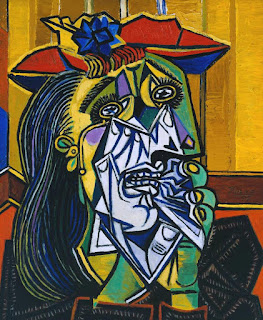

| Work by Bharti Kher |

After reading my article titled ‘Why Indian Art is also ‘White Middle Class (Fe)Male and English’, a French art scholar asked me what would be my take on the exhibition titled ‘Facing India’ to be opened on 29thApril 2018 at Kunstmuseum in Wolfsburg, Germany. I had not noticed anything about this exhibition so I had to go for an immediate google search which directly took me to the museum site and now I have enough ‘materials’ to speak a few words about it. Besides, the moment I hit on the page of the museum site that speaks about the exhibition, ‘Facing India’ I understood why my respected friend from abroad put such a question to me. I could see the broad stroke that the curator/s have drawn or how wide they have casted the net to catch more or less everything that could come under a title ‘Facing India’. This is a six women artists’ show and they are namely Bharti Kher, Mithu Sen, Reena Saini Kallat, Vibha Galhotra, Prajakta Potnis and Tejal Shah. Hence, the exhibition has to have the ‘feminine’ responses to the problems faced by India today or to put it in other words, these responses should be telling the viewer how these artists ‘face India’ today. Or rather, it could be the curatorial take on how as curators they ‘face’ India today.

‘Facing’ is an act that poses and solves a problem at once. When you have a problem you either run away or you face it. By facing it you are not simply looking at; you are trying to find ways to overcome the hurdle that the problem has posed or find ways to negotiate with the issues presented by it. And this facing to solve or overcome cannot be a value neutral act and therefore it is not value neutral facing in itself poses a counter problem which the existing problem would not like to ‘face’ at all. What would the original problem (which is not a response to anything but a self created one for its own advantages) do then to ‘face’ the problem/s created by the facing act of someone or more people? It could either try to finish of the problems not really by addressing the problems but directly decimating the posers or by putting them into serious disadvantage (look at Shabnam Hashmi and Teesta Setalvad as social activists who have dared to face some problems in the society. They have completely been disadvantaged by the original problem creators) or the original problem creators could really avoid or neglect the existence of such problems created by the ‘facers’ (that’s how often happens when commercial movies try to highlight social problems or artists try to face an issue by ‘portraying’ it in their works of art. For example, how many policy makers have taken the displacement issues painted over and over by the artists living in Gurugram, former Gurgaon, the IT suburb of Delhi, seriously and bullet pointed in their policy discussion or how many water conservationists have taken the artists who have raised the water crisis posed by many artists? I do not want to say that these artists have been completely neglected by the policy makers but I intend to say that the voices raised them are seen and heard as faint voices aesthetically managed in controlled environments exactly the way stunt directors performs death defying stunts and explosions in controlled environments. I do not think that in India, such stunts are seriously taken by Military intelligence or surveillance agencies as the film makers and Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) do not really collude in script writing as they marginally do in the case of Hollywood Sci-Fi movies).

|

| Work by Vibha Galhotra |

So first of all my response to this exhibition that such a theme, Facing India is not going to create any impact in the Indian sub-continent as an aesthetical project only because it is propped up in a German museum. But it would definitely make some polite circle high-fives because they have their vested in these artists as the future market investments. What surprises me in the curatorial decision to select six women artists to deal with such a vast subject like ‘India’ (Facing India is just a by-product) and trusting their whole faith in the aesthetics of these artists to deal with a volley of questions that they raise at the outset itself. From the website of the museum let me quote the questions: ‘How do women artists in India use their voices today? How do they deal with their social responsibility? Which language do they find for that which remains unsaid?’ Let me say, they are very potent questions. But my only problem is whether these artists are capable in ‘facing’ these questions or rather have they been ‘facing’ these questions in their practices at all. In my view (which is often critical therefore condescended by many market forces as pessimistic), these artists have not dealt with these issues seriously before and the best way to understand this is to closely watch their aesthetics over a period of time.

Art historians and critics at times become forensic experts (it implies that artists commit crimes and leave some palpable evidences at the crime site). Here, I get a forensic evidence right from the curators themselves (or what I take as a curatorial introduction from the note posted beautifully and proudly on the website of the museum). “Nevertheless, as broad as their range of topics may be, explicit and implicit references to the presence of the feminine and the position of women, as well as solidarity and empathy, are recurring themes throughout the exhibition.” What surprises me in this statement is the choice of words that the curators have carefully used (I can see their precarious standing while using those terms); ‘references to the presence of the feminine and the position of women’. Here, exactly the way these artists have used in their works, the presence of ‘feminine’ and ‘position of women’ appear without any political or critical qualification. In India there are thousands of women artists who exactly articulate the ‘feminine’ and the ‘position of women’ with great solidarity and empathy with their sisters but never making a political position in the issues that have generated such ‘feminine’ and ‘position of women’ responses. What distinguishes these artists from those thousands of women artists is their supposedly political positioning along with the ‘feminine’ position.

|

| Work by Reena Saini Kallat |

The non-appearance of the word ‘feminist’ in the whole text of the introduction juts out as an invisible sore-thumb. I do not say that there is a thumb rule in the museum discourse that any female oriented exhibition should be nailed to a plank of feminism/s. However, I cannot overlook the fact that any artist who shows ‘empathy’ and ‘solidarity’ with a gender group or a race, or a politically dispossessed people and so on, it automatically brings the artist to a political platform and a political platform cannot work on the humanist ideology alone, which is romantically idealistic and ideologically hollow and vacant. So in the case of women’s issues, the empathy and solidarity shown by a group of six artist cannot go ideologically free therefore a feminist position of any kind becomes a pre-requisite in its presentation (may be at this stage the curators may come up and say that in their full-fledged catalogue there are discourses on feminism vis-à-vis these artists). I am surprised why this particularly loaded term, ‘feminism’ is conveniently avoided from the introduction especially in the case of these six artists in India. I am sure that the curators have not noticed anything ‘feministic’ about these artists. If they have not found they have found the reality. It is unfortunate that Indian women artists who have got their global currency desist from using the feminist qualification in order to present their works of art. They still understand feminism as a burn bra movement, family breaking movement, free sex movement and catching others’ husband movement. Because of these reasons most of them do not like to qualify themselves as feminists. I should not be using this as a blanket accusation or qualification for all the women artists in India. We have Nalini Malani who has openly spoken about her feminist sympathies, Navjot Altaf, who has not only spoken about her feminist position but also her early Marxian activism to substantiate this, Shakuntala Kulkarni, to certain extent has spoken of feminism, Rekha Rodwittiya also has taken a feminist position but without understanding the theoretical nuances of it, a lack that has turned into an unfriendly person (that for the Indian public underlines the features of bad feminist – or rather feminists are bad position) and so on. Shilpa Gupta has very subtly politicized her feminist political position vis-à-vis the larger politics of the country. But ironically, the six artists mentioned above have not made clear political positioning in the society and hardly any feminist discourses in this country have taken their art for furthering the discourse in the visual arena. To put it simply, we do not have a Mahashweta Devi in visual art.

What could be the reason why the Indian women artists turn their face away from the feminist positioning? There are two major reasons; one, they have not studied feminisms with all their socio-political and cultural nuances. They have not done any field studies (except a few). This has made most of them closet feminists and socially ‘feminine’ artists, with their married lives and sindoor in their hair parting ‘intact’ (here I may be judged chauvinistic). But I could prove it with a recent interview of feminist artists from all over the world in some Biennale platform where one of the senior artists, Neelima Sheikh very politely shirking off the feminist mantle off her shoulders. The second reason is they think that ‘feminism’ is a foreign import and it does not work in the way it has worked in many other countries. So the Indian women artists could remain ‘feminine’ but never feminist, but empathize with feminist cause without ever being ‘called’ feminists. That’s exactly the reason why this exhibition has to bring in Urvashi Bhutalia, a feminist publisher with a strong grounding on the partition narratives as one of the essay writers for the exhibition. I would see it as an external justification of feminism which is not aesthetically seen in the works of the artists.

|

| Work by Mithu Sen |

Now let me come to the point that I had discussed in my previous essay (why Indian artists are white middle class and English). The present set of artists too is ‘white middle class and English’. They are in the words of the curators, “Socialized and educated, in an increasingly globalized world, these women artists no longer limit their ‘border controls’ solely to India, but rather reach out into other countries and continents.” What better definition is needed to prove that they are savvy artists with ‘white’ skins (notionally), middle class origin and English. The curators themselves say that they are globe trotters and jet setters and they reach out into other countries and continents. That is not a problem at all. We read world literature, watch global movies, listen to international music, east foreign cuisine, patronize world fashion so why not reach out to other countries and continents in return? As said, it is an increasingly globalized world. But in an increasingly globalized world, to reach out one has to resort to a mono-cultural attitude, accepting certain hegemonies of cultural practices and yield to it. It has to do away with pluralistic uncouthness to a large extent in order to be really global where brands are identified, attitudes are entertained and the same taste and same language are preferred. If you look at the visual language of these six artists in question, we could easily make out that all of them are catering to the aforementioned global qualities. They visualize and execute the ‘issues’ in a language which is understood globally. But we are forgetting to extend that sentence; understood globally by who? Their language could be understood by a tribe of people who use the same currency of culture. Everything has to be polished to the taste of the polite world that put on accents of different kinds depending on the occasion.

One may suddenly think that I am talking this done to death issue of indigenousness and Indian-ness in art. Some may even think that it is all about taking the whole argument to the 1960s and 1970s when everyone was looking for a visual language which would at once give you an identity and a passport. But today, the identity and passport have become the ability of an artist’s language to be global to be recognized in any part of the world; in any part of the world by the people who belong to a particular cultural class. It discriminates the people and artists who are dealing with the issues that are closer to home and touching to the lives of the common people all over the world. The curators have made a wonderfully ignorant statement in this context. Let me quote: “The rapid development of urban India thus runs contrary to the living conditions in rural areas. Countless ethnicities, castes, languages, cultures, religions and philosophies from an ostensibly pluralistic society, in which identity is defined by differentiation from the respective other. The social structure of India thus reflects that of our global community as a whole, which basically struggles with the same issues.” I say this is an ignorant statement mainly because of the reasons that I am going to discuss in the following paragraph.

|

| Work by Prajakta Potnis |

First of all the pluralism of the people in India is not just based on ethnic racial differences or mere linguistic differences as seen in the case of the ethnic differentiations that we see in other parts of the world. India’s pluralism is not even based on the economic differences experiences within the country and the curators have taken ‘poverty and struggle’ as a global currency where the deprived people from all over the world suffer from the same ‘poverty and struggle’. This difference is not even the working conditions and the conditions of women in general in any such vertically and horizontally graded societies. India’s problem is not simply because of its North-South or East-West divide. India’s issues are not pertaining to the memories of India’s partition or the present Hindu-Muslim divide. While corporate militarism has made many parts of the world into ruins, which has resulted into huge demographic displacements and dispossession, massive human tragedies and so on, Indian reality is not really connected to those things. The curators have seen the global struggles as the struggles between classes and genders (a common fallacy that we see in the western curators). Though they mention the caste issues and the untouchability still prevalent in India cursorily, they do not have the ability to see it as the fundamental organizational problem of Indian society which the artists in question have conveniently over looked. I do not say that each woman artist is supposed to look at the caste issues and the gender issues within the castes, I insist that the global language that these artists have developed do not have anything to do with the reality of women or the women issues in India. Even if an artist like Bharti Kher goes and takes the body castes of the sex workers in Kolkata and exhibit them, they are not far different from the aesthetics created by a white male artist like George Segal.

Now I would say why these artists in their efforts to sophisticate and polish the visual language and present them as globally relevant, have failed utterly in their ‘feminine’ as well as ‘feminist’ cause and deprived the women folk in their country of ‘empathy and solidarity.’ It has a peculiar economic reason. India ‘faced’ the market boom somewhere between the commencement of the new millennium and the global meltdown in 2008. India could push the market dynamics a bit more till 2012. India’s contemporary art developed and flourished during this time. This was not an India centric market and it never would have been imagined so. As globalization was the only one reason for the porous borders and the global flow of economics, the wares that were sold out in the market had to have global appeal and the global sophistication, devoid of the rough edges of the local histories and sensibilities. Market is money and money is always male. Market works according to the male values though there have been many female players and decision makers in the market. But the aesthetics produced in those days (even today) was/is absolutely global and catering to the global male who did not want to look at poverty and struggle, menstrual blood or lack of sanitary napkins, rapes or murders or men and women and such ‘petty and disturbing’ issues. Even if the artists wanted to handle those issues they had to come with polished devises to create such aesthetics. Thukral and Tagra, Princess Pea, Subodh Gupta, Sunil Gawde and so on are the best examples of such aesthetics. It is easy to mention a few more names such as Jitish Kallat, Sudarshan Shetty and Shilpa Gupta. One could see how the rest of the artists in India who got market success remained ‘international yet national’ but only a few ‘really international’. The six artists who ‘grew up’ in this climate polished their language to those levels that could be passed off as ‘truly international’; that means they carry a sort of male language, globally understood, un-disturbing and not particularly pitching on any of the ‘home bound issues’.

|

| Work by Tejal Shah |

These artists have definitely pin pointed certain issues as their ‘pet issues’ and could make claims that they have been ‘facing it’ for quite some time. But the sad condition is that except for one artist none of them is ever discussed for the serious socio-gender or cultural discourses taking place in India today. If at all they are invited to discuss these issues, it always happens in the polite crowd that often agrees with each other and keeps the issues as something to be discussed over wine and cheese. I have never come across these artists responding to the burning issues in India in any manner. They may be doing it in their house parties, which who else not doing in India! None of these artists has in any way contributed to the general discourse of socio-political issues in India. There are many other artists in the meanwhile doing research and practical works among the people who are really going through problems. They take clear political positions but art is never hailed as ‘global’ for the lack of sophistication and too much presence of local issues. These six artists could ‘face India’ in their own terms which is not a problem at all; but it would not make any difference to any of the discourse currently on in India because their aesthetics is White Male Middle Class and English, which is absolutely a minority in India and except for the aspirant majority of the artists, rest of the population is not even aware of their existence.

(Images taken from Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg website)